After days of diligent pouring, I have finally waded across 750 pages of paradoxes, logic, philosophy, mathematics, painting, music, and computation and crossed the checkered flag signaling the end of Hofstadter's 'Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid.' Why, you might ask, is this important? Well, in the field of 'intelligent, thought provoking books', GEB has a towering, almost bullying, presence. It is the Don Bradman of 'intellectual' writing. Consequently it manages to scare off the reader even before it begins, partly owing to the lofty goals it sets out in the beginning, and partly because of the sheer thickness that requires negotiation. And now that I am done, I at least want to jot down some of the ideas which have managed to stick, for the fear of losing them again.

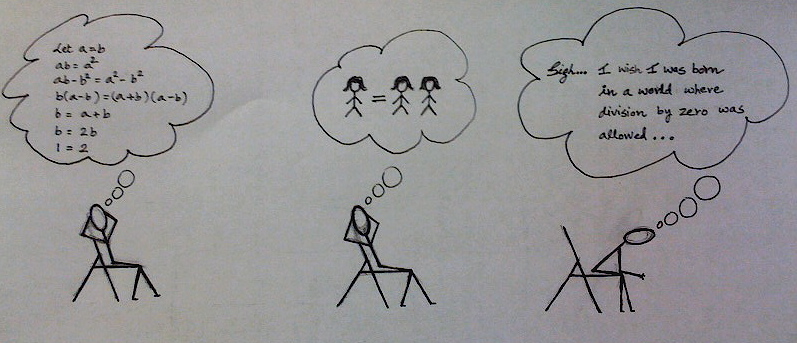

What is it about? For a book that deals with issues as different as molecular biology and transcendental music, it has a surprisingly clear and single minded focus. I wonder if anyone who has read it finds that the book is about anything but one single sentence and its ramifications. Epimenides paradox is the sentence:

'This sentence is false'.

No matter how much you think about it, it won't make sense. There is something deeply sinister and pathological about the sentence. But it's just language and language can be easily pushed under the rug. It doesn't bring the house down. GEB primarily tells the story of this dude called Kurt Godel who devised a way of applying this sentence to mathematics in the first half of the 20th century. He showed that for a sufficiently complex formal system (like number theory) there is a way to formulate a theorem which is true in that system and which says:

'I am not a theorem in this system'.

In other words, he proved that a mathematical system which aims to be consistent (no self contradictions) will not be able to provide proofs for all that is true within that system, and that a system which aims to give proofs to all truths within it is necessarily inconsistent. If you think about it, a result of this depth does indeed require a 750 page tome to talk about it. I mean, results and theorems in every other discipline are merely humanity's tentative, though increasingly accurate, stabs in darkness. They do and will continue to suffer from our own sensory limitations. Experimental validations of our grandest astronomical theories and minutest quantum ones are merely smudges on photographic plates. On the other hand, theorems in mathematics stand alone, almost inviolable (almost). And a theorem about how mathematics can and will behave should truly count as the towering achievement of human intellect. It should also be seen as one of the greatest contributions to society because mathematics is the language we have chosen to interpret the world in. It is the only tool we have got and it is precisely because of it that society affords us the comforts and leisure which allow us to indulge our creativities, and be sympathetic towards fellow humans, animals, nature.

The book goes on to study the implications of the theorem and its curiously self-referential nature on issues like the mysteriousness of the human mind, the future of artificial intelligence, the meaning and emergence of truth and beauty in artistic creations, the existence/nonexistence of free will, the illusion of intelligence resulting from a system of sufficient complexity, genetic evolution etc. The scope of the book is breathtakingly broad and the fact that Hofstadter makes it all appear coherent is either because he is a depressing genius in deception or because deep down, things should be so. Like Hardy mentioned about Ramanujan's crazy results: 'They must be true because, if they are not true, no one would have had the imagination to invent them.'

I found that the book, despite its content and size, is cheerfully lucid. It has the same 'philosophical displacement' as David Deutsch's 'The fabric of reality' but while Dr. Deutsch assumed that all his readers trace their route back to Einstein and decided to cram everything in 200 pages, Hofstadter is more sympathetic to our vacuity. He has included fictional dialogues between Lewis Carrol's characters Tortoise and Achilles which give a simple-worded, though cryptic, overview of the ideas. And he has shown elaborate harmonies between mathematics, painting (M.C.Escher, Rene Magritte) and music (J.S.Bach) to sustain a general curiosity. But then, he hasn't done all this for the express desire sustaining interest. He has done it because, as you start feeling by the end of the book, there is a very deep connection between such disparate fields. It shouldn't come as a surprise that what we find harmonious in music and beautiful in art, often has deep mathematical associations. When music is bound in meters and beats, and art has familiar geometries, when poetry is enclosed in metered iambs, it seems that a condition for beauty is automatically met. This, as opposed to postmodern art, aleotoric music, which, in order to explain their significance, have to invoke ideas of rebellion, boredom, authority and conformity. Where such deep connections exist between mathematics and art, it is interesting to see how something as profound as Godel's Incompleteness and self-reference commute between the two. And this is what GEB explores, with humor and intelligence.